|

One of my graduate school professors, Dr. Janaki Natarajan, regularly challenged her Social Identity students with two simple questions that reliably test what we think we know:

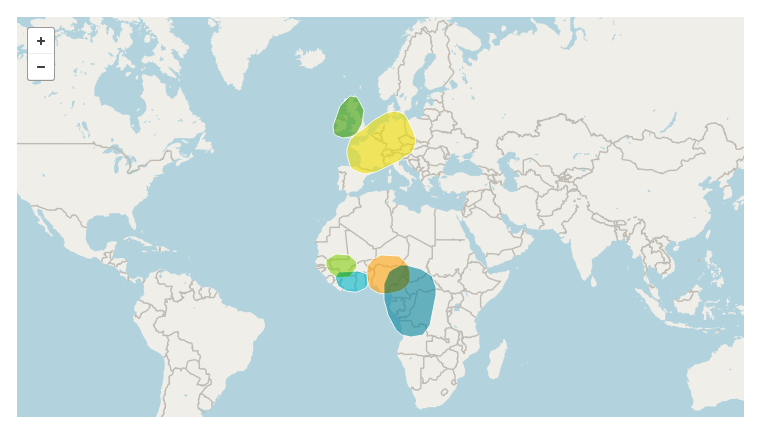

In the 12 hours since receiving ethnicity results from my DNA analysis, these are two of the few processing questions I’ve managed to ask myself. After a dozen years of working across cultures of all kinds and feeling unfulfilled by limited knowing of my own ethnic origins, I’ve been at a loss in recent hours about how to make meaning of the raw data linking me to what might have been home in an alternate series of historical events. (See image above for a visual snapshot of my genealogy results by country/ region.) For whose benefit, after all, have I felt the need to identify ethnically? And, what purpose do my ethnicity results serve? A global diversity client recently shared my cynicism about the commercialization of culture. Trending on social media at the time was a few-minute video clip of various people’s emotional reactions as their DNA-based ethnicity data were revealed to them. I’d watched it from my laptop screen and felt inspired to journey on my own “DNA discovery”. Of course, after I fell in love with the characters’ stories, the video turned out to be a damn advertisement. In discussing the commercial with my client, we agreed that a false claim was made; that simply tracing the lines of descent from our ancestors does not create cultural belonging. It’s when what's within the lines of our descent are colored by lived experience that we truly belong—in both the collective consciousness of the in-group and our own minds. While culture is of benefit to the individual, it is built for the group. Thus, this Chicagoan is not Central or West African because she read a report this morning stating that 18% of her genealogy links back to Cameroon, 16% to Côte d'Ivoire and 10% to Nigeria. Taking on an identity that is not my own may positively promote business interests, but it does not offer me the benefit of belonging. "Whatever culture of the rainbow you represent, you, too, are enough to enter into the discussion on diversity— as you are." Still skeptical about what the DNA results might reveal, I spit into a test tube and sent it off to a San Francisco P.O. Box for testing. As a Black woman born and raised stateside, intrigued by intercultural communication, often under-represented in global diversity circles and over-represented in national diversity circles, I expected that knowing my ethnicity would help define my place in dialoguing on diversity. When others shared family traditions rooted in specific cities or regions of long-established nations outside U.S. borders, I regretted that I could only say my folks were from Mississippi. I’d wanted something more to leverage my blackness.

So far, it turns out that my ethnicity results have served the purpose of grounding me more deeply in my racial and regional identities. I am a Black/ brown woman from the central region of the States whose ability to speak on national cultures and their sub-cultures is nuanced by my experiences along the periphery of ethnic identity. Whether or not I ever came to know that I am of Irish (13%) and Western European (10%) blood, I hold an equally valid—and even unique—position in understanding the complexity of race-based, ethnic and national cultures because I represent a people who was mixed and made in America. I am enough as I am. Whatever culture of the rainbow you represent, you, too, are enough to enter into the discussion on diversity as you are. For whose benefit will you engage between the differences that matter—and for what purpose? Let’s talk! Virtually yours, Malii Brown [i] According to Ancestry.com, the saying, “Kiss me, I’m Irish", likely originates from an age-old legend that kissing the stone in the medieval Blarney Castle in Ireland— or an Irish person in lieu of the stone— will give one the power of eloquent and persuasive speech—and luck! Subscribe to receive blog posts delivered fresh monthly into your inbox at [email protected].

4 Comments

8/8/2016 05:22:52 pm

VERY interesting! Not knowing usually presents a burning curiosity so the test does serve the purpose of quenching that fire. Knowing ones ancestry, supports the understanding that to be against other ethincities/cultures means being against ones self. Whether or not the results are accurate, the mind is stretched...never to return to it's original outlook.

Reply

8/8/2016 06:27:11 pm

Thank you for the compliment, @Mae Parrish! Agreed that once the mind is stretched, the outlook also remains expanded. As far as understanding "other" ethnicities and cultures as our own, I'd add that we are all one human race, separated by a fraction of a percentage of DNA and united by common history and experience. In the most basic sense then, there are no "others".

Reply

3/5/2019 07:28:05 pm

Cultural diversity is one of the topics I love talking about, with people who have the same interest as mine. Though we are all united to become one, there are indeed differences we can observe yet we will still have the urge to choose to become one. Differences might be there all the time, but it's not enough reason for us to stop and fight. Understanding and camaraderie is what we need in order for us to achieve world peace. At the same time, respect plan a huge role too!

Reply

4/9/2019 02:34:40 pm

@BestEssayService: We certainly have one thing in common: Cultural diversity is one of the topics I love talking about with people, as well! Simultaneously, I like your idea that we are all, in fact, united, and are in the process of becoming one.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

EngageBetween...people. place. purpose. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed